The Whitechapel Gallery is keen – and quite rightly – to rehabilitate Hannah Hoch, the ‘forgotten’ female protagonist of Berlin Dada. True, Hoch has until recently been left out of official histories of the movement – written by men, the gallery notes; however, her fall into relative obscurity seems to owe just as much to the cruel twist of fate that brought the Nazis to power at the height of her career as to a misogynistic art world.

The vaguely chronological show begins with a number of Hoch’s charming early textile and embroidery designs which demonstrate an angular modernism in soft pencil or watercolour, a feminine cubism similar to that of Sonia Delaunay, who also designed textiles. That a designer of fabrics should be branded as a feminine occupation, however, seems already anachronistic. Raoul Dufy, for example, a Post-Impressionist of some renown, famously designed textiles for the luxury producers Bianchini-Ferier, which were used at fashion houses such as Poiret and in many ways epitomise Parisian style in the twenties. Equally, Hoch used the techniques and approach acquired in this medium to produce daringly abstract Dada pieces that effectively challenge the boundaries between textile design and pattern-cutting, and ‘fine art’ – for instance in ‘Tailor’s Flower’ (below, 1920).

The feminist account continues as Hoch discovers collage (or photomontage). It may well be true that she owed her acceptance by the Berlin Dada group to her relationship with Raoul Hausmann, and that her work would not otherwise have been exhibited with them; but was this purely misogyny? In the event she had a large photomontage work (entitled ‘Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany’) displayed in a prominent position at the First International Dada Fair in 1920.

Hoch herself had the archetypal look of the ‘New Woman’ of Weimar Berlin, with her cropped dark hair and fringe and androgynous clothes. But in contrast to many modern women who adopted this look to shock, Hoch was far from exhibitionist, rejecting this facet of the Dada movement.

Her early collages – such as ‘Flight’ (right, 1931) – are amusing and witty, but with a strongly acerbic undercurrent. As with all satire, however, it is difficult now to grasp the full power of the image, rooted as this genre inevitably is in the specific social, political and cultural issues of its time. The faces would have been cut from contemporary periodicals, newspapers and magazines, the personalities who grabbed the headlines now impossible to guess. Features and limbs are with great precision excised from their original contexts and combined with parts of animals, statuary, or other natural forms to create fantastical grotesques, composed – often very simply – into a ‘nonsense narrative.’ These creations have the imaginative brilliance of an Edward Lear poem, but recalling their direct link to the immediate reality of Weimar Berlin imbues this creativity and sharp aesthetic sense with a major force, an unnerving but inexplicable impact that follows the initial laughter.

Her early collages – such as ‘Flight’ (right, 1931) – are amusing and witty, but with a strongly acerbic undercurrent. As with all satire, however, it is difficult now to grasp the full power of the image, rooted as this genre inevitably is in the specific social, political and cultural issues of its time. The faces would have been cut from contemporary periodicals, newspapers and magazines, the personalities who grabbed the headlines now impossible to guess. Features and limbs are with great precision excised from their original contexts and combined with parts of animals, statuary, or other natural forms to create fantastical grotesques, composed – often very simply – into a ‘nonsense narrative.’ These creations have the imaginative brilliance of an Edward Lear poem, but recalling their direct link to the immediate reality of Weimar Berlin imbues this creativity and sharp aesthetic sense with a major force, an unnerving but inexplicable impact that follows the initial laughter.

‘Made for a Party’ (left, 1936) emphasises the painted lips and exaggerated blond curls that were a prerequisite for the ideal Aryan woman. Below, the healthy, sportive figure is another desirable characteristic of German womanhood. At the bottom is the eye, the symbol of intellect and understanding, relegated to the lowest level of importance and about to be kicked out of the picture entirely by the shapely athletic leg. On the other hand, it may just as well be a critique of interwar Berlin’s dissolute hedonism, masking its desperate desire to ignore the economic and political chaos that threatened to engulf Germany – the open eye that perceives this being rejected by the inviting grin of the cabaret dancer.

‘Made for a Party’ (left, 1936) emphasises the painted lips and exaggerated blond curls that were a prerequisite for the ideal Aryan woman. Below, the healthy, sportive figure is another desirable characteristic of German womanhood. At the bottom is the eye, the symbol of intellect and understanding, relegated to the lowest level of importance and about to be kicked out of the picture entirely by the shapely athletic leg. On the other hand, it may just as well be a critique of interwar Berlin’s dissolute hedonism, masking its desperate desire to ignore the economic and political chaos that threatened to engulf Germany – the open eye that perceives this being rejected by the inviting grin of the cabaret dancer.

The series ‘From an Ethnographic Museum’ broadens Hoch’s expression of her fears and concerns regarding the position of women in Weimar society – and the pernicious effect of an exploding media culture dictating modern ideas of female ‘beauty’ – to explore the concept of beauty across ages and cultures. This is pure satire, the sharp juxtaposition of a primitive sculpture with a contemporary model showing by means of their contrasting exaggerations quite how ridiculous and distorted these visions are.

This untitled image from the series (above, 1930) caps a static torso with a seductively relaxed head and arms, the hieratic and the intimate collide – yet the objectification of the half-naked woman remains unchanged through time. They are far from being humourless feminist statements however; all are saturated with a sense of fun, of playing consequences or dressing up subversive paper dolls.

Other images from the series more subtly combine the features of Egyptian or Aztec and modern woman. Some of these, and the subsequent, stitched-together images of children, are mildly disturbing with their suggestion of mutilation and reconfiguration of dismembered features. Post-First World War, recent victims of a newly mechanised warfare were much in evidence, and the science of plastic surgery advanced in tandem. It is actively uncomfortably to be confronted by the distress of the bawling child, something is indefinably wrong and slightly sinister…

Other images from the series more subtly combine the features of Egyptian or Aztec and modern woman. Some of these, and the subsequent, stitched-together images of children, are mildly disturbing with their suggestion of mutilation and reconfiguration of dismembered features. Post-First World War, recent victims of a newly mechanised warfare were much in evidence, and the science of plastic surgery advanced in tandem. It is actively uncomfortably to be confronted by the distress of the bawling child, something is indefinably wrong and slightly sinister…

In these grotesque malformities there is also the echo of the ‘freak show’, a tendency that re-emerged in the nightclubs and cabarets of Berlin, where those considered ‘abnormal’ by polite society could satisfy every whim. The androgyny of the ‘New Woman’ was equally considered a threat to moral norms, and Hoch’s genderless – or multi-gendered – figures stridently attack such values which increasingly had no place in a modern post-war world. Women had taken over men’s jobs as more and more were conscripted into the trenches, while the fighting generation had become disillusioned by the previously accepted values that had led to such massacre and destruction.

Then there are the overtly political collages. ‘Heads of State’ (above, 1918-20) shows the Weimar President Friedrich Ebert and Gustav Noske, the minister of defence, in swimming trunks against a childishly doodled background taken from an embroidery pattern. Caught off-guard and undressed, they appear both vulnerable and risible, the title pointing up the sharp incongruity between this appearance and their official roles. ‘High Finance’ (below, 1923) uses the incisive juxtaposition of the photomontage technique to criticise the collaboration between German financiers and arms manufacturers, as representatives of these dour old men trample Germany’s cities beneath their feet. They are clearly to blame, in the eyes of the younger generation, for all the irreparable damage of the recent war. The effectiveness of satires such as these make clear the threat that Hoch must have posed to the Nazi regime. Her work was branded degenerate, and she took refuge in a quiet suburb on the edge of Berlin to see out the next ten years in silence.

The war and Nazism stands like a hiatus, a gap in time, as one climbs the stairs; in the upper gallery the second war is over and colour bursts upon the scene. These collages revel in the saturated tones of post-war advertising and magazine features, and in the pure abstract forms that emerge from their arbitrary dissection. It is tempting to pass by with little more than a glance, so much less meaningful do they appear in contrast to the early works.

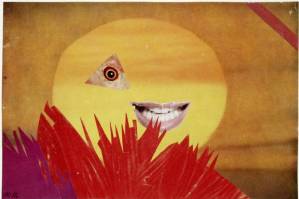

Bizarrely, some show more affinity to synthetic cubism, looking back to this forerunner to the collage technique in c.1912; others take on a surrealist character, tending less to the Dada-surrealism of Ernst, and more towards the amused post-card collages of Roland Penrose – notably the floating fish eye and smiling lips (left) that seem amused by the joke they are playing on their audience. It is a joyful art, reflecting the lifting of political tensions and the ideological extremes of the interwar years, and enjoying (with an amused cynicism) the consumerist ‘paradise’ that the 50s heralded – literally, in the fabric of the collages themselves, a riotous surfeit of shiny, glossy forms.

Bizarrely, some show more affinity to synthetic cubism, looking back to this forerunner to the collage technique in c.1912; others take on a surrealist character, tending less to the Dada-surrealism of Ernst, and more towards the amused post-card collages of Roland Penrose – notably the floating fish eye and smiling lips (left) that seem amused by the joke they are playing on their audience. It is a joyful art, reflecting the lifting of political tensions and the ideological extremes of the interwar years, and enjoying (with an amused cynicism) the consumerist ‘paradise’ that the 50s heralded – literally, in the fabric of the collages themselves, a riotous surfeit of shiny, glossy forms.

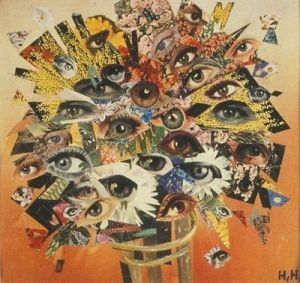

The ‘Bouquet of Eyes’ (right) exemplifies the excess – while also recalling Weimar cinema, and the ‘male gaze’ that blurs into a mass of eyes as the the robot Maria in Metropolis begins her seductive dance… Here the eyes are deprived of their power, tied up with string and presented to the post-war woman, now in thrall to the colour supplements and another ideal of feminine beauty that she sees as somehow autonomous.

Hannah Hoch sums up her career very satisfactorily for the curators with a large autobiographical collage; it is quirky, self-deprecating and humorous, her sharp and amused eye turned on her own life and enjoying the view.