A scream echoed faintly through the gallery. A Hollywood scream, a scream with just the right element of terror, but perfectly controlled like the heroine’s perfectly set hair and flawless dress. A fitting soundtrack to the beautiful painted demons and femmes fatales, to the picturesquely ugly monsters that lurked within tenebrous canvases. The source turned out to be a clip from Murnau’s ‘Nosferatu’ (1922), one of several films illustrating the cross-media appeal of the gothic horror genre that provides the thematic narrative to this wide-ranging exhibition.

Sub-titled ‘Dark Romanticism from Goya to Max Ernst’, the Musee d’Orsay has gathered a wonderfully various display running from the late eighteenth century to the height of surrealism in the twentieth. We begin with Fuseli’s satan being chased away by Ithuriel, with manic expression but physically classical beauty; he is the fallen angel. And John Martin’s ‘Pandemonium’, a truly apocolyptic scene, the human presence impotent before a sea of flame and the immense, foreboding, monolithic edifice on the other side.

The literary inspiration presiding at the birth of dark romanticism came from Dante and Milton; Bouguereau makes this debt explicit in his salon painting of the two authors in hell, while Blake, famous for his illustrations of ‘Paradise Lost’, is represented instead by his powerful image of Satan – ‘Red Dragon’ – intended to illustrate the Book of Revelation.

Round a corner and the focus changes, from imposing oil paintings to smaller pictures, etchings, drawings and objects, and from evil in human form – if classicised – to monsters of the imagination. Delacroix’s ‘Mephistopheles’ hovers with glee, admiring his talons, above the gables and spires of a sleeping town; Victor Hugo’s castle sits atop a rain-swept promontory with gothic foreboding.

I had never realised that Hugo drew so prolifically in addition to his writing, but his ink sketches reveal the extent of his dramatic imagination – especially the ‘Main Benisseur de l’Abesse’ which looks like the antecedent of Quentin Blake’s illustrations of ‘The Witches’, talons bared.

These evil creatures are juxtaposed with a series of paintings of the ‘victim’, the pure, alabaster-skinned damsel, fainting with terror. Ary Scheffer, it appears, was particularly good at depicting this character, the pale flesh of his Lenore – from Poe’s paean to the death of a young woman – glowing amidst the shadowy depths of the landscape as she is swept away towards her terrible fate by an exotic man on horseback. Paul Delaroche, best known (to me) for the ‘Execution of Lady Jane Grey’ in the National Gallery, contributes another melodramatic picture of an expiring female.

Witches, sorcerers and nightmares follow, and here Goya’s blackest imaginings come into their own, with a series of images from ‘Los Caprichos’ such as the night terrors in ‘The Sleep of Reason produces Monsters’ and the painting ‘Witches Flight’ in which the hovering coven appear in the dream of the shrouded figure below, as with their tall hats of the Inquisition they torture their prey. While prints from ‘The Disasters of War’ series reveal a more real and immediate horror.

These are joined by an oil sketch of Gericault’s famous ‘Raft of the Medusa’, the suggested cannibalism of the shipwrecked crew highlighted as an example of the depravity that humans can descend to in extremis; and Delacroix’s ‘Sabbat des Sorcieres’ with firelit hordes gathering by night on a hillside with gaunt gothic ruins silhouetted in the background.

Then the landscape takes over, a sense of foreboding achieved by vast empty spaces frozen in dread anticipation, by the sudden void of an abyss or by the oppressive weight of crumbling cloisters. Any anonymous figures are secondary: the trail of black figures filing through the ruined archway in Friedrich’s painting are barely distinguished from the gravestones and tree stumps that surround them, dark against the snow; the sleeping figure in Carl Blechen’s ‘Gothic Church Ruin’ almost absorbed into the rapacious moss.

Symbolism saw the revival of such irrational, unconscious fears expressed in paint and sculpture in the late nineteenth century. Interestingly, the female suddenly takes over as the figure of evil intent; in the context of a teeming urban and industrial society it is suggested that this phenomenon might be rooted in a fear of prostitution and venereal disease. At the same time nature, traditionally represented as female, came to be perceived as a devouring force as ideas of Darwinian evolution and social degeneration took hold. Femmes fatales figures such as Eve, Salome and Medusa appeared repeatedly in the imagery of this period – Gustave Moreau’s ‘Salome’ is typical both of the artist’s predilection for biblical and mythological subjects and of this fin-de-siecle obsession with decadence.

Munch’s ‘Vampire’ expresses the same fears, though where Salome is bejewelled and raven-haired with a crystalline profile, exuding a callous potency, the red-headed vampire appears soft in outline and warm in her embrace. She is almost comforting the faceless man… but perhaps that was itself the great dread, that in the age of decadence men might literally have their strength sucked out of them through the misguided embrace of a fallen women.

My two top paintings in the following room were Duvocelle’s ‘Crane aux Yeux Exorbites’ – a cheeky skull peering over a wall, with the added comedy of a frame decorated with bones – and Felicien Rops’ ‘La Mort au Bal’ where death is having a fabulous time in drag, scrawny ankle flirtatiously bared and bony hand on hip.

Then the were some empty landscapes, dark and misty in the tradition of Friedrich, but now transposed to the urban park, to the age of electric light. However, in Spilliaert’s inky ‘Dyke at Night’ or Degouve de Nuncques’ ‘Nocturne in the Parc Royal, Brussels’ this enhances, if anything, the sense of unease and shadowy ambiguity.

In the final section we jump a few more years to Surrealism. The recourse to dark romanticism was once again a reaction to the trauma of reality, this time a post-World War I reality in which all values previously upheld unquestioningly were proved hollow and the old social order absurd. The Surrealists revelled in the abandonment of reason, giving prominence to chance, dreams and the unconscious. However, their debt to their dark romantic inheritance becomes clear. Dali is compared to Bocklin, his realism tinged with something inexplicable and disturbing. Elsewhere, Hans Bellmer’s imagery of mutilated or dislocated dolls recalls the cruel and twisted eroticism of de Sade; these should really have been shown side by side with Jeandel’s cyanotypes of women bound or trussed up with rope – these explicit early examples of S&M look out of place among the symbolists who deflected such predilections (or fear of them) onto a mythological or imaginary world. Or indeed alongside the other early photographic exhibits that attempt to manipulate the new medium to suggest ghostly visitations or the appearance of ectoplasm during seances – these are merely amusing, not disturbing.

The figure of the mannequin and the idea of ‘convulsive beauty’ were central preoccupations of the Surrealists. Mannequins, much like Bellmer’s dolls, were considered ‘phantom object-beings’ (in Dali’s words), symbols of the eroticism and the idealised female form harnessed by consumer culture.

Brassai also engages with surrealist ideas – in this case the ‘found object’ and the ‘chance encounter’. His photographs of graffiti seem to look back to the monstrous apparitions of Delacroix or Goya, nightmare imagery of the unconscious which is here transposed literally onto the fabric of the modern city.

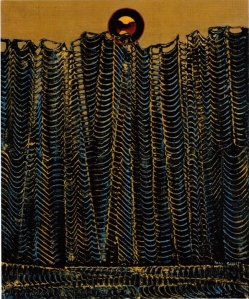

Meanwhile Ernst’s ‘Foret d’Arêtes’ updates the dark romantic landscape tradition, the gothic horror of the German forest represented by a dense accumulation of drill-bit-imprinted tree-trunks that threaten to prevent any escape from this nightmarish fairy-tale of the modern industrial age.

And so a century and a half of artistic engagement with the dark recesses of the imagination is brought to an end. Not that we will ever abandon the genre entirely while we still have an active imagination and human propensity for fear – though now it seems to play out more frequently on our TV screens in the format of a drama series or murder mystery. But behind and alongside the visual stands the written word – evoked by occasional quotations stretching across the gallery wall – Shakespeare, Milton, Mary Shelley, Walpole, Ann Radcliffe, Poe, Baudelaire, the brothers Grimm, de Sade, J.K. Huysmans, Andre Breton… In ‘A Rebours’ (1884), which Huysmans described as ‘a wild and gloomy fantasy’, the protagonist imagines the mental journey of that disillusioned modernist Baudelaire:

“[Baudelaire] had finally reached those districts of the soul where the monstrous vegetations of the sick mind flourish. There, near the breeding ground of intellectual aberrations and disease of the mind – the mysterious tetanus, the burning fever of lust, the typhoids and yellow fevers of crime – he had found, hatching in the dismal forcing-house of ennui, the frightening climacteric of thoughts and emotions.”