The photographs are still and meditative. There are vast desert landscapes, sweeping architectural panoramas, austerely beautiful monochrome still lifes; even the portraits show faces frozen in reflection. Yet the unifying theme is one of war and conflict, whose concomitant chaos, terror and misery would appear far removed from the peace and beauty of many exhibits here.  This is what makes Tate Modern’s approach to war photography so intriguingly different – it follows a chronology of temporal distance, the first pictures taken moments after an event, the final images almost a century later. Another factor is that these are all ‘art’ photographs – they are not the ‘captured in action’ shots of a front-line paparazzi – and even if they appropriate documentary, ‘found’ or snapshot images, these are presented in such as way as to detach them from the moment.

This is what makes Tate Modern’s approach to war photography so intriguingly different – it follows a chronology of temporal distance, the first pictures taken moments after an event, the final images almost a century later. Another factor is that these are all ‘art’ photographs – they are not the ‘captured in action’ shots of a front-line paparazzi – and even if they appropriate documentary, ‘found’ or snapshot images, these are presented in such as way as to detach them from the moment.

Luc Delahaye’s picture of US bombing on Taliban positions in Afghanistan (c.2001, top) and Toshio Fukada’s ‘The Mushroom Cloud’, taken seconds after the atomic bomb hit Hiroshima in 1945, are the starting point. Don McCullin’s shell-shocked marine in Vietnam (1968, left) is captured moments after the action, rigid and staring unseeing at the camera.

Luc Delahaye’s picture of US bombing on Taliban positions in Afghanistan (c.2001, top) and Toshio Fukada’s ‘The Mushroom Cloud’, taken seconds after the atomic bomb hit Hiroshima in 1945, are the starting point. Don McCullin’s shell-shocked marine in Vietnam (1968, left) is captured moments after the action, rigid and staring unseeing at the camera.

Two priests are photographed by Pierre-Anthony Thouret standing amid the wreckage of Reims cathedral in the days and weeks after the First World War (pub.1927, right), while an angel looks out in horror and pity over the ruins of Dresden after allied raids in 1945 (above right). Similarly, Simon Norfolk documents the architectural destruction of warfare in the Karte Char district of Kabul in 2001-3; a bullet riddled cinema at the Palace of Culture stands abandoned, and a battle scarred apartment building quietly collapses as a flock of sheep continue on their way (below).

Taken in the months after the first Gulf War, Sophie Ristelhueber’s series of images of Kuwait – ‘Fait’ (1992, below) – fill the next room. They alternate aerial scenes of almost abstract, pockmarked desert landscapes or burning oil fields at night with close-up shots of abandoned clothing hanging off the parapet of a makeshift entrenchment, commenting on the dislocation between the technological and the human in modern warfare.

A year on from the 2011 revolution in Libya, Diana Matar returned to produce ‘Evidence’, a series of photographs documenting the buildings or locations where atrocities had taken place under the Gaddafi regime. Mostly taken at night these deserted urban wastelands throb with the uneasy ghosts of the ‘disappeared’ and those summarily executed. And further on in sub-Saharan Africa Jim Goldberg chronicles the  aftermath of war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo through portraits of refugees and former rebels in ‘Open See’, and Jo Ractliffe records the effects of Angola’s civil war in images of mines and military facilities still littering the landscape – as well as the part surreal, part sinister ‘Roadside stall on the way to Viana’ (2007, left).

aftermath of war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo through portraits of refugees and former rebels in ‘Open See’, and Jo Ractliffe records the effects of Angola’s civil war in images of mines and military facilities still littering the landscape – as well as the part surreal, part sinister ‘Roadside stall on the way to Viana’ (2007, left).

Looking back a decade or so, Taryn Simon addresses the Srebrenica massacre during the Balkan Wars by means of a family tree composed of photographic portraits of those surviving, with accompanying text and visual ‘footnotes’ reinforcing the concept of a scientific process. Walid Raad – or ‘The Atlas Group’ – uses a similarly detached approach to document decades of conflict in Lebanon between 1975 and 1991; media pictures of the engines remaining from car bombs that exploded throughout Beirut during this time are framed, annotated, and arranged in a grid structure across the gallery wall.  Like Raad, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin are known for appropriating images and re-presenting them in such a way that they articulate a political critique of the control or manipulation of images in the press, revealing them in a different light. Here the images have been selected from the Belfast Exposed Archive documenting the Troubles in Northern Ireland, where coloured dots were used to mark those selected for use.

Like Raad, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin are known for appropriating images and re-presenting them in such a way that they articulate a political critique of the control or manipulation of images in the press, revealing them in a different light. Here the images have been selected from the Belfast Exposed Archive documenting the Troubles in Northern Ireland, where coloured dots were used to mark those selected for use.

Various photographers were drawn to Berlin in the 1960s as the Berlin wall was constructed, segregating East and West Berlin. Don McCullin was one, capturing American soldiers looking across the wall from empty window embrasures, as well as East German guards on the other side of the barbed wire (1961, below).

Michael Schmidt continues the narrative in 1980, showing a post-war Berlin still marked by undeveloped spaces of urban wasteland a few rooms further on in the chronology.

Meanwhile, Paul Virilio’s ‘Bunker Archeology’ (1975) contemplates the remnants of German defences along the coast of France, and Jerzy Lewczynski’s ‘The Wolf’s Lair’ creates a semi-abstract modernist study of the bunker that acted as Hitler’s HQ in Poland as he planned his attack on the Eastern front.

Then we return to the fall out of the atomic bomb in Shomei Tomatsu’s portraits of scarred faces and silent objects – such as this tin helmet to which a fragment of bone has been fused by the heat of the blast (1963, left). Later in the exhibition, Portuguese artist Joao Penalva creates a more abstract response to Hiroshima over fifty years after the event;

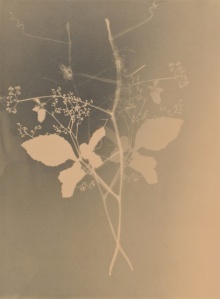

Then we return to the fall out of the atomic bomb in Shomei Tomatsu’s portraits of scarred faces and silent objects – such as this tin helmet to which a fragment of bone has been fused by the heat of the blast (1963, left). Later in the exhibition, Portuguese artist Joao Penalva creates a more abstract response to Hiroshima over fifty years after the event;  his solarised photograms of small weeds found growing in a building that survived the blast comment on the intense heat that left ‘shadows’ of living things imprinted on buildings, echoed by the solarisation process (‘From the Weeds of Hiroshima – Cayratia Japonica’, 1997, right) .

his solarised photograms of small weeds found growing in a building that survived the blast comment on the intense heat that left ‘shadows’ of living things imprinted on buildings, echoed by the solarisation process (‘From the Weeds of Hiroshima – Cayratia Japonica’, 1997, right) .

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg is a contemporary photographer whose conceptual images in series – sparse and austere like the ‘industrial archaeology’ of Bernt & Hilla Becher – explore meaning and history through architecture; here, the Kuchatov nuclear test site in Kazakhstan (2012, left). An-My Le also returns decades later to a site of conflict – and one that was once home – taking photos of contemporary Hanoi decades after fleeing the Vietnam war as a child (1994-8, below).

Fifty years on, the debris of war has been swept from the surface; yet the hidden fragments that remain still have a sometimes touching, sometimes haunting, power. Nick Waplington’s photographs of the graffiti of German prisoners of war in Wales – ‘We Live as we Dream, Alone’, 1993; faint drawings of pine trees and lakes, fragments of germanic script – are on the scale of the walls themselves and so highly detailed that the plaster might almost be crumbling before our eyes. Julian Rosefeldt explores former Nazi headquarters in Munich, now schools and colleges of music, whose untouched vaults and basements retain an air of oppression and secrecy.

Luc Delahaye’s ‘Patio Civil, Cementero San Rafael, Malaga’ (2009, right) takes the archaeological approach a step further, no longer simply suggesting the atrocities that once occurred in seemingly guileless landscapes and buildings, but capturing the indisputable evidence of slaughter in a mass grave dating from the Spanish Civil War. Stephen Shore, in contrast, has produced studies of some of the survivors of the holocaust and war in the Ukraine, focusing on the small domestic details of their lives and the few gaudy but prized possessions, the composite effect a testimony to stoicism and almost unbearably moving.

Luc Delahaye’s ‘Patio Civil, Cementero San Rafael, Malaga’ (2009, right) takes the archaeological approach a step further, no longer simply suggesting the atrocities that once occurred in seemingly guileless landscapes and buildings, but capturing the indisputable evidence of slaughter in a mass grave dating from the Spanish Civil War. Stephen Shore, in contrast, has produced studies of some of the survivors of the holocaust and war in the Ukraine, focusing on the small domestic details of their lives and the few gaudy but prized possessions, the composite effect a testimony to stoicism and almost unbearably moving.

Chloe Dewe Mathews brings the show to a close with suitably silent and empty landscapes, landscapes replete with history and memory. The images in ‘Shot at Dawn’, pale light illuminating damp green fields or a frosty copse, ask us to think back a hundred years and imagine each unblemished scene as the site of an execution for cowardice. Mathews carefully documents the site and the names of the soldiers – as in this image of Verbranden-Molen, West-Vlaanderen, where four soldiers were shot on 15th December 1914.

The exhibition acts as a reappraisal of how we perceive war and conflict, and how this gradually alters over time. It reveals the indelible scars that war inflicts upon a landscape or upon the living organism of a city and its inhabitants. It shows the human capacity for evil, often from a detached – almost scientific – angle, but also the human capacity to persevere regardless, to heal and rebuild, to purge or come to terms with the memories of horror. As the introductory quotation from Kurt Vonnegut, who inspired the exhibition, reads:

‘People aren’t supposed to look back. I’m certainly not going to do it anymore. I’ve finished my war book now. The next one I write is going to be fun. This one is a failure, and had to be, since it was written by a pillar of salt.’

‘People aren’t supposed to look back. I’m certainly not going to do it anymore. I’ve finished my war book now. The next one I write is going to be fun. This one is a failure, and had to be, since it was written by a pillar of salt.’

P.S. The Archive of Modern Conflict is a postscript, an annexe, to the exhibition – but a treasure trove and not to be missed.