The Pallant House Gallery in Chichester has achieved a duel triumph with ‘Sickert in Dieppe’. The exhibition is both a focused study of the development of Sickert’s technique and a biography of the artist and the city as both underwent seismic change during the turbulent years of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It brings together many disparate works that I had never seen before and which revealed a different side to Sickert’s life and work.

The Pallant House Gallery in Chichester has achieved a duel triumph with ‘Sickert in Dieppe’. The exhibition is both a focused study of the development of Sickert’s technique and a biography of the artist and the city as both underwent seismic change during the turbulent years of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It brings together many disparate works that I had never seen before and which revealed a different side to Sickert’s life and work.

Whistler was the first great influence on Sickert, who left the Slade to work as his ‘apprentice’. Whistler’s motto was “we have only one enemy and that is funk”; his method was to work ‘wet on wet’ with thin oil paint, which demanded confidence as there was little margin for error. When done well this gave a smooth surface and subtly graduated tonality. Some of Sickert’s small early oils on panel (which he called ‘sunlight pochades’ – pocket sized and completed en plein air), such as ‘La Plage’ (c.1885, above) and ‘The Harbour, Dieppe’ (c.1885, top), are very Whistlerian in this respect. The panel is unprimed, so that the colours have a muted quality and yet retain an enigmatic resonance.

Whistler was the first great influence on Sickert, who left the Slade to work as his ‘apprentice’. Whistler’s motto was “we have only one enemy and that is funk”; his method was to work ‘wet on wet’ with thin oil paint, which demanded confidence as there was little margin for error. When done well this gave a smooth surface and subtly graduated tonality. Some of Sickert’s small early oils on panel (which he called ‘sunlight pochades’ – pocket sized and completed en plein air), such as ‘La Plage’ (c.1885, above) and ‘The Harbour, Dieppe’ (c.1885, top), are very Whistlerian in this respect. The panel is unprimed, so that the colours have a muted quality and yet retain an enigmatic resonance.

Sickert knew Dieppe from an early age; his mother had been to school there and returned with her small children for holidays. In the 1880s Whistler travelled to Dieppe with Ellen Cobden (whom he married in 1885). Through Whistler, Sickert was introduced to the French Impressionists, and formed a particularly close rapport with Degas. ‘The Red Shop (The October Sun)’ (c.1888, above left), a small oil on panel, shows a new approach to colour with its vibrant geometric planes of vermilion against soft ochre tones – it has all the impact of a Rothko in miniature. If anyone inspired the use of such daring tones it was Degas; he uses the same shade in ‘Miss Lala at the Cirque Fernando’, completed just a few years before the two artists met.

Sickert knew Dieppe from an early age; his mother had been to school there and returned with her small children for holidays. In the 1880s Whistler travelled to Dieppe with Ellen Cobden (whom he married in 1885). Through Whistler, Sickert was introduced to the French Impressionists, and formed a particularly close rapport with Degas. ‘The Red Shop (The October Sun)’ (c.1888, above left), a small oil on panel, shows a new approach to colour with its vibrant geometric planes of vermilion against soft ochre tones – it has all the impact of a Rothko in miniature. If anyone inspired the use of such daring tones it was Degas; he uses the same shade in ‘Miss Lala at the Cirque Fernando’, completed just a few years before the two artists met.

Degas also encouraged more structure in Sickert’s compositions, and a greater emphasis on the human and the architectural. ‘The Laundry Shop’ (1885, right), on a similar scale to ‘The Red Shop’, shows in the nearby preparatory drawing the technique of ‘squaring up’ that Sickert now adopted and which is visible in much of his later work, a technique based on the Renaissance practice of transferring designs from cartoons to frescos on a vast scale. It is also closely cropped, like a snapshot of everyday life taken in passing – another Degas-esque trait that perhaps stemmed from the fashion for Japonisme in the late 19th century, particularly the elongated and stylised woodblock prints.

Degas also encouraged more structure in Sickert’s compositions, and a greater emphasis on the human and the architectural. ‘The Laundry Shop’ (1885, right), on a similar scale to ‘The Red Shop’, shows in the nearby preparatory drawing the technique of ‘squaring up’ that Sickert now adopted and which is visible in much of his later work, a technique based on the Renaissance practice of transferring designs from cartoons to frescos on a vast scale. It is also closely cropped, like a snapshot of everyday life taken in passing – another Degas-esque trait that perhaps stemmed from the fashion for Japonisme in the late 19th century, particularly the elongated and stylised woodblock prints.

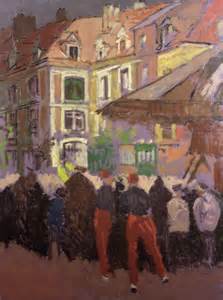

Larger paintings of this early period include ‘The Fair at Night’ (1902-3, left) which is much freer in execution, as if Sickert is sketching directly onto canvas. The shadowy, silhouetted foreground giving way to bright sunlit architecture beyond would become something of a feature in Sickert’s Dieppe paintings. ‘L’Hotel Royal, Dieppe’ (1894, below) is quite different, a beguiling, mysterious painting with no movement or noise and unsettling, slightly sickly, shades of mauve and peppermint green. It embodies the melancholy of dusk and the end of summer.

Larger paintings of this early period include ‘The Fair at Night’ (1902-3, left) which is much freer in execution, as if Sickert is sketching directly onto canvas. The shadowy, silhouetted foreground giving way to bright sunlit architecture beyond would become something of a feature in Sickert’s Dieppe paintings. ‘L’Hotel Royal, Dieppe’ (1894, below) is quite different, a beguiling, mysterious painting with no movement or noise and unsettling, slightly sickly, shades of mauve and peppermint green. It embodies the melancholy of dusk and the end of summer.

Appropriately perhaps, the Decadent poet Arthur Symons dedicated the following verses to Sickert – they sum it up beautifully…

Appropriately perhaps, the Decadent poet Arthur Symons dedicated the following verses to Sickert – they sum it up beautifully…

The grey-green stretch of sandy grass,

The grey-green stretch of sandy grass,

Indefinitely desolate;

A sea of lead, a sky of slate;

Already autumn in the air, alas!

One stark monotony of stone,

The long hotel, acutely white,

Against the after-sunset light

Withers grey-green, and takes the grass’s tone.

Listless and endless it outlies,

And means, to you and me, no more

Than any pebble on the shore,

Or this indifferent moment as it dies.

Other landmarks of Dieppe were painted with equally restrained drama. ‘Le Grand Duquesne, Dieppe’ (1902, above right), a statue of the Dieppois navel hero, is depicted in silhouette as the façade behind is bathed in evening sunlight. The church of Saint Jacques was one subject that Sickert returned to countless times (an example of c.1899-1900, right). These paintings have been compared to Monet’s series of Rouen Cathedral, but there is less interest in the changing effects of light and season than in technical experimentation – some are loosely handled, some tightly squared up; some use a bright peach-coloured ground, some darker; some use the separated brushwork of Impressionism, some the flat planes of Symbolism.

Other landmarks of Dieppe were painted with equally restrained drama. ‘Le Grand Duquesne, Dieppe’ (1902, above right), a statue of the Dieppois navel hero, is depicted in silhouette as the façade behind is bathed in evening sunlight. The church of Saint Jacques was one subject that Sickert returned to countless times (an example of c.1899-1900, right). These paintings have been compared to Monet’s series of Rouen Cathedral, but there is less interest in the changing effects of light and season than in technical experimentation – some are loosely handled, some tightly squared up; some use a bright peach-coloured ground, some darker; some use the separated brushwork of Impressionism, some the flat planes of Symbolism.

In 1898, after separating from Ellen, Sickert began a relationship with the Dieppoise fishwife Augustine Villain and soon after moved in with her. He became very fond of her small horde of children and of the simple working class life. ‘Les Arcades de la Poisonnerie’ (c.1900, left) was next to the fish market where Augustine worked and was a view that Sickert painted several times during this period.

In 1898, after separating from Ellen, Sickert began a relationship with the Dieppoise fishwife Augustine Villain and soon after moved in with her. He became very fond of her small horde of children and of the simple working class life. ‘Les Arcades de la Poisonnerie’ (c.1900, left) was next to the fish market where Augustine worked and was a view that Sickert painted several times during this period.

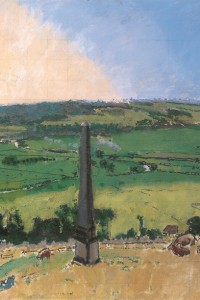

When war was declared in 1914 Sickert was living in the countryside outside Dieppe with his second wife, Christine (nee Angus), a pupil whom he had married in 1911. The happy pre-war years at the Villa d’Aumale at Envermeu inspired Sickert to paint landscapes again; his tones became lighter and paint thinned after a period using a more impasto style during the Camden Town paintings of the late 1910s. ‘The Obelisk’ (1914, below left) is one such idyllic landscape, though the curator Katy Norris points

When war was declared in 1914 Sickert was living in the countryside outside Dieppe with his second wife, Christine (nee Angus), a pupil whom he had married in 1911. The happy pre-war years at the Villa d’Aumale at Envermeu inspired Sickert to paint landscapes again; his tones became lighter and paint thinned after a period using a more impasto style during the Camden Town paintings of the late 1910s. ‘The Obelisk’ (1914, below left) is one such idyllic landscape, though the curator Katy Norris points  out the symbolism of this war memorial being painted just as war was looming once again – Sickert had struggled with the perspective of this picture and, using this analogy, declared that he could only deal with ‘one war at a time’. Another similarly bucolic scene of corn stooks is also given more sombre significance; harvesting was stopped as conscription papers were issued, the stooks themselves seeming to presage the serried ranks of soldiers who had disappeared from the fields.

out the symbolism of this war memorial being painted just as war was looming once again – Sickert had struggled with the perspective of this picture and, using this analogy, declared that he could only deal with ‘one war at a time’. Another similarly bucolic scene of corn stooks is also given more sombre significance; harvesting was stopped as conscription papers were issued, the stooks themselves seeming to presage the serried ranks of soldiers who had disappeared from the fields.

Back in Dieppe, Sickert painted ‘Café Suisse, Dieppe’ (1914, above right), a typical scene of sunlit facades from a shaded arcade; but here too the war makes itself felt, with soldiers recognisable by their red and blue uniforms and schoolgirls in their straw hats, perhaps preparing to return to England.

The Sickerts had to return too for the duration of the war. However, they returned to Envermeu as soon as it was over and regained their quiet country life. In 1920 the Sickerts bought a house, the Maison Mouton; the occasion is recorded by Sickert’s lovely lamp-lit portrait, ‘Christine Drummond Sickert, nee Angus, buys a Gendarmerie’ (c.1920, right) – for the house had indeed a chequered history, as a gendarmerie, a horse dealer’s and an inn: the bedrooms were all numbered. Tragically, Christine’s tuberculosis began to worsen again and she died shortly after moving into their new home.

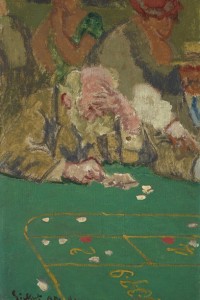

Ever since returning to Envermeu (‘The Happy Valley’ as he titled it on his etchings) Sickert had made forays into Dieppe, frequenting the cafes chantants and the casino. Now he could no longer bear the scenery of Envermeu that was so deeply connected with Christine – ‘[the landscapes] are like still-born children’, he wrote – and moved into an apartment in the town. He took up figure subjects again, picking out, with shades of Degas’ absinthe drinkers, the down-and-outs on the fringes of society. ‘The System’ (1924-6, left) picks out just such a character who, amidst the anonymous crowds, is caught in a moment of private desperation.

Ever since returning to Envermeu (‘The Happy Valley’ as he titled it on his etchings) Sickert had made forays into Dieppe, frequenting the cafes chantants and the casino. Now he could no longer bear the scenery of Envermeu that was so deeply connected with Christine – ‘[the landscapes] are like still-born children’, he wrote – and moved into an apartment in the town. He took up figure subjects again, picking out, with shades of Degas’ absinthe drinkers, the down-and-outs on the fringes of society. ‘The System’ (1924-6, left) picks out just such a character who, amidst the anonymous crowds, is caught in a moment of private desperation.

‘Au Cafe Concert, Vernet’s Dance Hall’ (1920, right) and ‘O Nuit d’Amour’ (c.1922, below) are two views Sickert made of this cafe concert which seem to position the artist – and with him the viewer – on the outside looking in; though full of lights and music the sense of melancholy is exacerbated by the empty tables in the foreground. Despite his grief, this final spell in Dieppe certainly proved fruitful; in his studio on the rue Aguado Sickert painted shadowy interiors akin to the Camden Town paintings, such as ‘The Prevaricator’ and ‘L’Armoire a Glace’, as well as one of his most striking portraits, of Victor Lecourt – ‘a superb creature’ – standing in Sickert’s apartment among the myriad patterns of the furnishings and with the Dieppe dusk framed though the window beyond, solid and erect.

‘Au Cafe Concert, Vernet’s Dance Hall’ (1920, right) and ‘O Nuit d’Amour’ (c.1922, below) are two views Sickert made of this cafe concert which seem to position the artist – and with him the viewer – on the outside looking in; though full of lights and music the sense of melancholy is exacerbated by the empty tables in the foreground. Despite his grief, this final spell in Dieppe certainly proved fruitful; in his studio on the rue Aguado Sickert painted shadowy interiors akin to the Camden Town paintings, such as ‘The Prevaricator’ and ‘L’Armoire a Glace’, as well as one of his most striking portraits, of Victor Lecourt – ‘a superb creature’ – standing in Sickert’s apartment among the myriad patterns of the furnishings and with the Dieppe dusk framed though the window beyond, solid and erect.

Sickert returned to London in early 1922, and though he visited Dieppe from time to time it was never again his home. The town deserves this dedicated exhibition; Sickert’s reputation is based excessively on the notorious Camden Town murder paintings – on the basis of this show, it should rest in Dieppe.